What “Avant-Garde” Really Means in Fashion

“Avant-garde” gets thrown around a lot in fashion, but where does it come from, and what does it actually mean? From its radical roots to its presence in lifestyle and design, here is what truly sets avant-garde apart from passing trends.

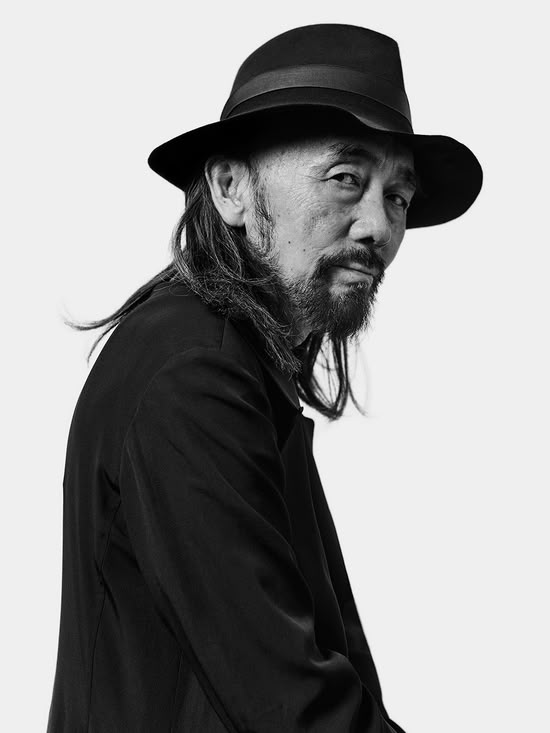

Say “avant-garde fashion” and a certain image probably pops into your head: mostly black outfits, raw edges, strange yet compelling silhouettes, maybe something that looks more like sculpture than clothing. Names like Rick Owens, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, or Margiela might come up too. But beyond dramatic looks and big names, what is avant-garde, really? Is it just a vibe, or is there something deeper going on?

Origins: From Art to Fashion

Let’s start with the basics: “avant-garde” comes from the French term for “advanced guard” or “vanguard,” originally a military term, but later used to describe artists and movements that challenge norms and push cultural, artistic, and societal boundaries. Over time, it’s grown to encompass a wide range of styles and philosophies, from realism to modernism and the many “-isms” that shaped 20th-century art.

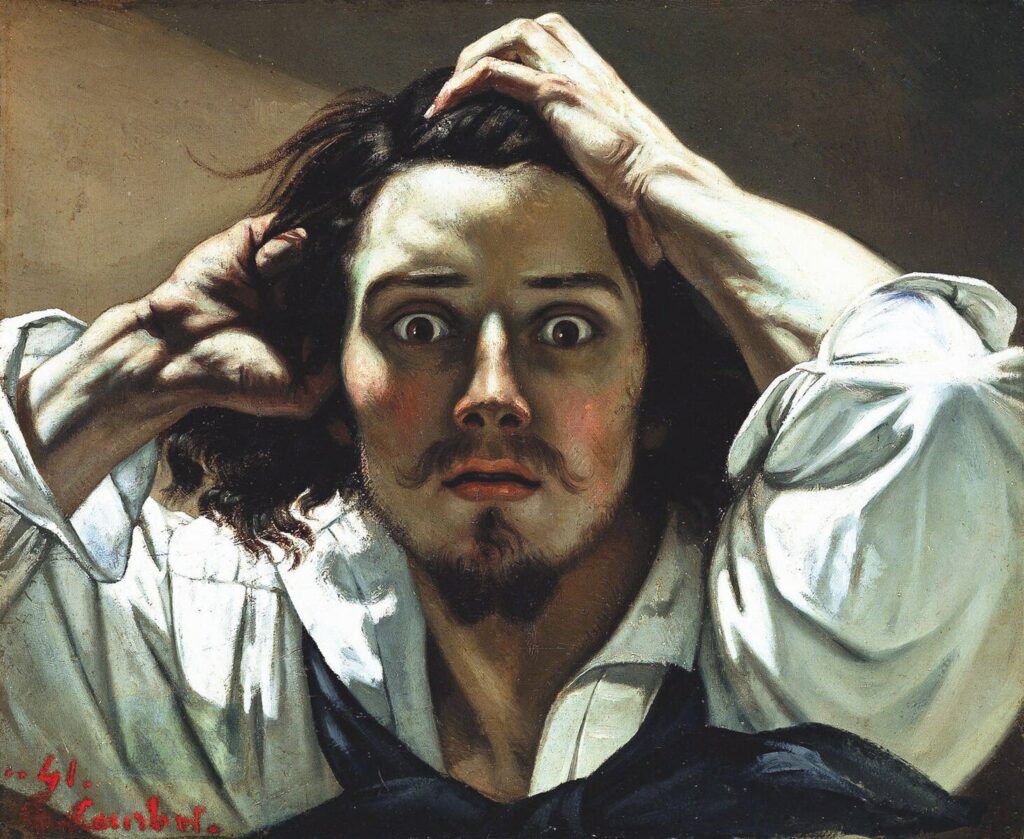

Gustave Courbet, Le Désespéré, 1843

The term first entered the arts in the 19th century through French theorist Henri de Saint-Simon, who believed that artists, like scientists and industrialists, should lead the way in transforming society. By the 1850s, avant-garde art began to take shape with the rise of realism. Artists like Gustave Courbet, influenced by socialist ideals, rejected traditional academic painting in favor of raw, grounded depictions of everyday life.

Russel Wright, Costume for Cubist Circus, 1923

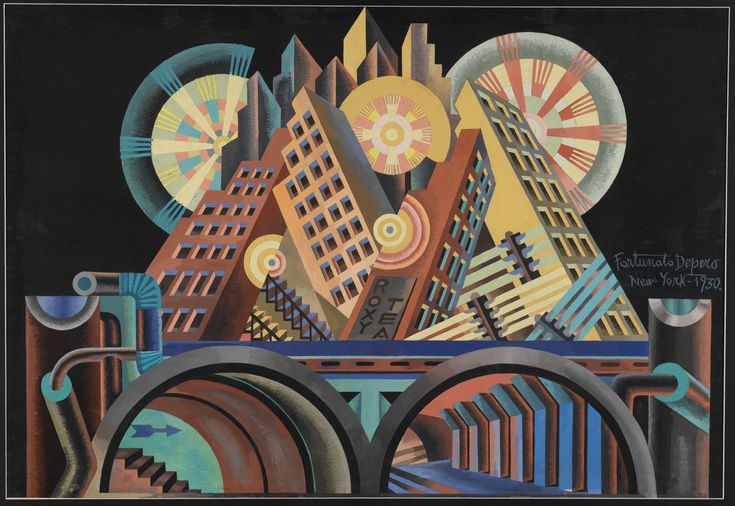

Grattacieli e Tunnel, Fortunato Depero, 1930

In the 20th century, the avant-garde label came to define movements like Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, and Constructivism, all of which broke away from convention and explored new ways of seeing and expressing the world. So how did this translate to fashion?

Fashion as Art and Critique

Avant-garde has profoundly influenced fashion by challenging traditional ideas of beauty, form, and function, transforming clothing from mere utility into a medium for artistic and political expression.

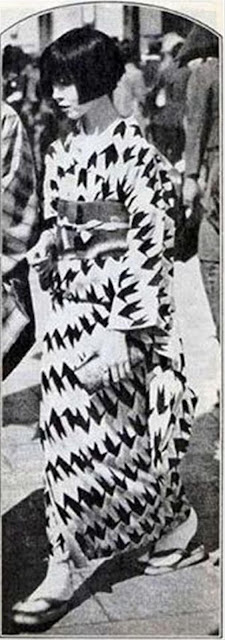

Moga in Kimono, 1920’s

Modern Girls with cropped hair in 1920’s

Its roots in fashion are complex, but many trace its early stirrings to 1920s Japan, where designers began experimenting with European silhouettes, creating garments that were either starkly geometric or intentionally shapeless. These designs played with proportion and structure in ways that hinted at a deeper, more conceptual approach to dress

Yohji Yamamoto by Neil Bedford, 2014

Rei Kawakubo by Timothy Greenfield, 1992

But it was in the 1980s that avant-garde fashion fully took shape on the global stage. Japanese designers like Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto disrupted Western fashion with radical silhouettes, deconstructed garments, and a refusal to conform to conventional ideas of beauty or gender. Their work positioned fashion as a space for critique, not just aesthetics, an ethos that still shapes the field today.

Just like in art, avant-garde fashion pushes boundaries. It questions what clothing is, how it should be made, and what it means to wear it. Many designers in this space use clothing as a visual argument, blurring the lines between garment, sculpture, and performance.

Movements like Dada and Surrealism, with their embrace of absurdity and rejection of logic, echo through avant-garde fashion’s distortion, theatricality, and subversion. Later, designers like Kawakubo and Yamamoto brought in the influence of conceptual art, disassembling garments and redefining the very idea of dress.

Core Values Born in the 1980s

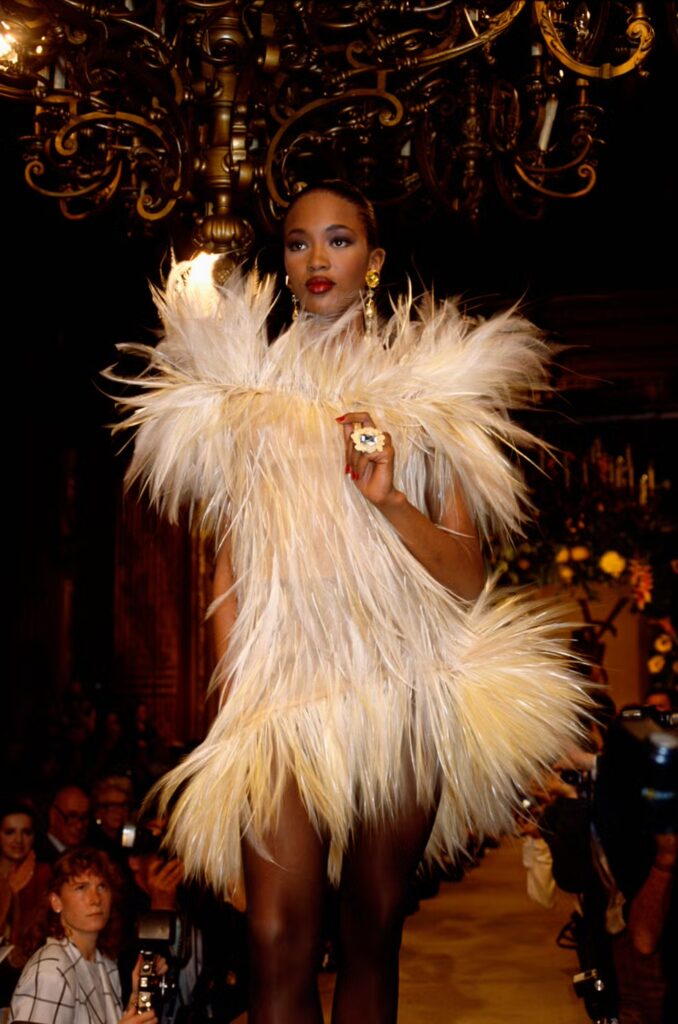

Naomi Campbell for Yves Saint Laurent, FW1987

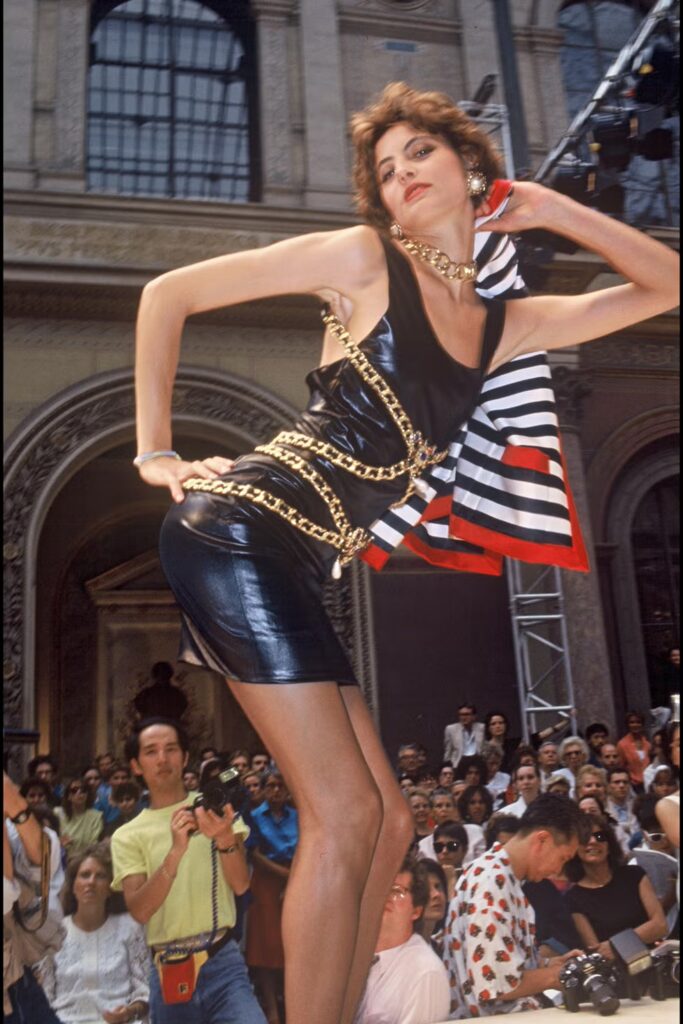

Ines de la Fressange wearing Haute Couture Chanel, FW1986

Every fashion movement is more than clothes; it’s about values shaped by its time. Avant-garde’s key values are rejecting commercialism, subverting norms, and embracing intellectual depth, which emerged strongly in the 1980s, a decade of contradictions: booming capitalism, flashy logos, and hyper-consumerism dominated Western fashion.

Avant-garde was a radical response to all that:

- Rejecting Commercialism

In a time of power suits and luxury branding, designers like Kawakubo and Yamamoto pushed back. Their clothes avoided obvious sex appeal or polish, making a statement that fashion could be critical, not just consumable. - Subverting Beauty and Gender Norms

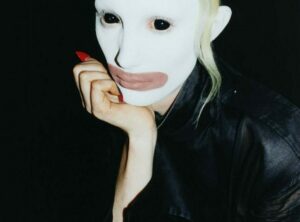

The 1980s were about hyper-gendered dressing: shoulder pads, bodycon, and masculine power dressing. Avant-garde dissolved those codes. Kawakubo distorted or hid the body, unsettling traditional femininity. Margiela erased identity altogether through anonymity and disguise, challenging the cult of the designer. - Intellectual and Cultural Critique

As postmodernism influenced art and academia, fashion followed. Avant-garde became conceptual, more like installation art than seasonal trends. Influenced by thinkers like Foucault and Derrida, designers embedded critiques of consumerism and identity into deconstructed garments and fractured narratives. - Embracing Imperfection

Rather than polished perfection, avant-garde embraced rawness: inside-out seams, asymmetry, distressed fabrics, reflecting the decade’s fascination with decay and authenticity - Emotion and Presence

While mainstream fashion emphasized image, avant-garde tapped into deeper emotions: silence, tension, discomfort. Kawakubo’s “Lumps and Bumps” collection made viewers confront deformity and unease, staging confrontation over fantasy.

Digital couture by Siyun Huang, “Shield of the Forest”

Jane Kovich wearing Comme Des Garcons, 2019

In essence, the 1980s were the perfect storm for avant-garde fashion, a resistance to glossy consumerism and an expression of deeper anxieties about identity and meaning.

“For something to be beautiful, it doesn’t have to be pretty.”

Rei Kawakubo (Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between, 2017)

Rei Kawakubo: Changing the Way We See Fashion

When Rei Kawakubo brought Comme des Garçons to Paris in 1981, she didn’t just present a new label; she challenged the entire fashion system. Her early collections were stark, mostly black, with torn edges, asymmetry, and oversized shapes that confused and even unsettled critics. Some called it “Hiroshima chic.” But that discomfort was the point. Kawakubo wasn’t interested in traditional beauty. She wanted people to rethink what clothing could mean.

Her 1983 collection pushed that further. The clothes didn’t flatter the body. They wrapped, hung, or draped in strange ways. In a decade full of glam and power dressing, her work felt quiet, raw, and deeply different. She once said, “For something to be beautiful, it doesn’t have to be pretty,” a line that still defines her approach.

Comme Des Garcons, SS97

One of her most talked-about collections came in 1997: Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body. The pieces were padded in unexpected places, turning bodies into distorted, unfamiliar shapes. It confused people, even made them uncomfortable. But again, that was the point. Why should fashion always follow the rules of beauty or symmetry?

Junya Watanabe, FW24

Kawakubo’s radical vision helped shift the fashion landscape, creating space for future avant-garde and experimental designers, like her protégé Junya Watanabe, to explore more conceptual, idea-driven approaches to clothing.

Instead of following trends, she created space for fashion to be strange, quiet, even confrontational. That’s what pushed avant-garde fashion from the edges of culture into something lasting. She didn’t just design clothes; she changed what fashion could say.

Why Avant-Garde Fashion Endures

Avant-garde fashion isn’t just another trend that comes and goes. It doesn’t follow the usual fashion cycle of seasons and hype. Instead, it’s more about a way of thinking, questioning, pushing boundaries, and reimagining what clothes can be and what they can say. Unlike trends that often focus on how things look on the surface, avant-garde fashion is driven by ideas, often connected to deeper cultural or personal themes.

Because of this, it tends to stay relevant over time. It doesn’t chase what’s popular; it often challenges it. While mainstream brands might jump on a popular cut or fabric, avant-garde designers are usually more interested in questioning why something is considered beautiful or why certain norms exist in the first place.

You might notice echoes of avant-garde ideas in more commercial fashion, even if the original message gets lost or simplified along the way. Still, it shows how these bold concepts can ripple out and influence the broader landscape.

Its ability to make us pause and think can make us uncomfortable or confused at first, but that’s part of the experience. In a world where trends change overnight and image is everything, avant-garde fashion offers something different. It’s more intentional, more reflective. It reminds us that fashion doesn’t have to be about fitting in; it can also be about breaking away, starting conversations, or imagining something new.

As Rei Kawakubo said, “Create your own world within the world.” That pretty much sums it up. Avant-garde isn’t just about clothes; it’s about ideas. Staying curious, taking risks, and not settling for what’s expected.

Credits

Written by Erica Zheng Jia Xin @br4in_f4rt