Issey Miyake

From the ashes of Hiroshima rose a man who chose not to speak of death, but to dress the world in life. Issey Miyake turned tragedy into light, scars into pleats, and made of fashion a hymn to movement, resilience, and rebirth.

There are beings whose very life is a victory over death, and whose art ardently celebrates the light of life. Issey Miyake is one of those. Born April 22, 1938 in Hiroshima, he was only seven when the atomic bomb reduced his city to ashes on August 6, 1945. The child survived the nuclear apocalypse, but his mother was grievously burned and died a few years later from her injuries. From the day of nuclear fire, little Issey carried within his body a fragility… a bone disease caused by radiation, but in his soul, he drew an extraordinary vitality from it. Emerging from the blaze, he made a silent vow to celebrate life through his work. Never, however, did he speak publicly of his suffering as a Hiroshima child. Instead of words, he let his clothes bear witness to his desire for rebirth and peace.

Irving Penn’s portrait Issey Miyake Fashion: Face Covered with Hair (1991) shows a model standing with her face entirely veiled by a cascade of long, sleek hair.

In the 1950s, young Miyake turned towards design. In 1958 he entered Tokyo’s Tama Art University to study graphic arts and fashion. It was a time of reconstruction and modernity for Japan. Miyake, eager to understand how forms are born, was particularly interested in the process of creating a garment. He already foresaw that clothing is architecture for the body, a space where movement and soul must freely express. Graduated in 1964, driven by thirst to learn from Western masters, he flew to Paris in 1965. In the French capital, he became an apprentice at Guy Laroche then an assistant at Givenchy, observing from inside the rituals of haute couture. In parallel, he took classes at the École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture to complete his training. Paris was a springboard for him: he discovered the rigor of the craft but also its shackles.

“My first years in Paris served as a springboard… at that time notions of beauty and the human body’s aesthetics were too rigid for me. Fortunately, perceptions were upended by the wind of freedom of 1968”

He later confided, he who had witnessed the May ’68 revolts and their questioning of norms.

Irving Penn and Issey Miyake’s collaboration (1983 onward) – Miyake’s early ’80s exhibitions and recognition

Armed with these experiences, Issey Miyake returned to Asia in the late ’60s, his heart set on an ideal of liberated fashion. He dreamed of an aesthetic that would descend into the street, accessible to all, far from the elitist confines of Paris salons. In 1970, back in Tokyo, he founded the Miyake Design Studio, whose workshop became his spiritual laboratory.

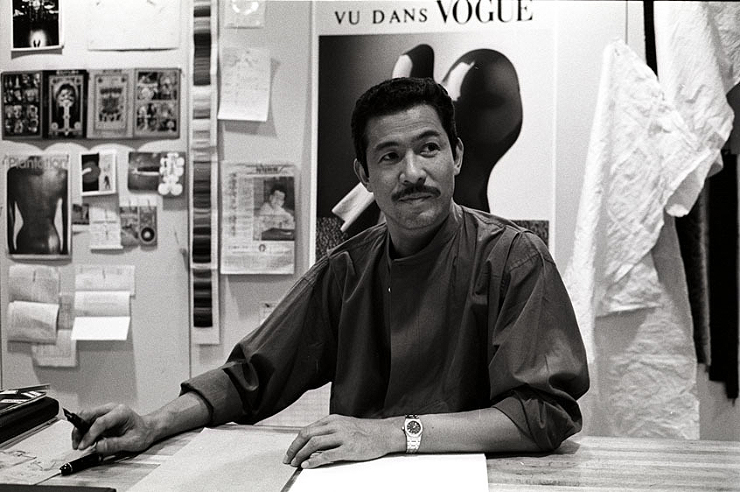

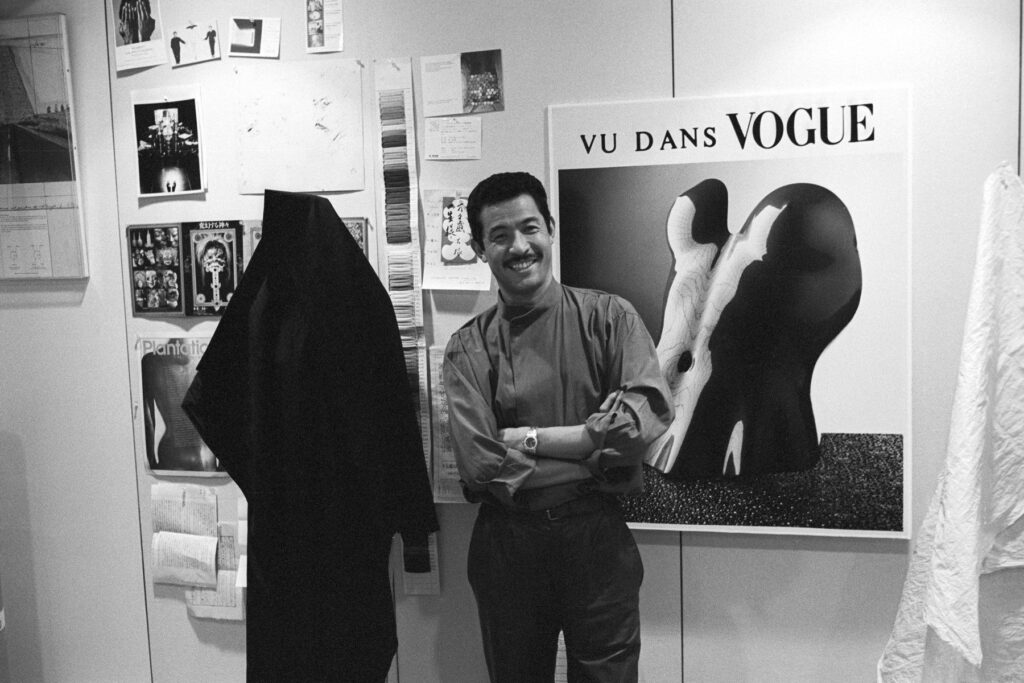

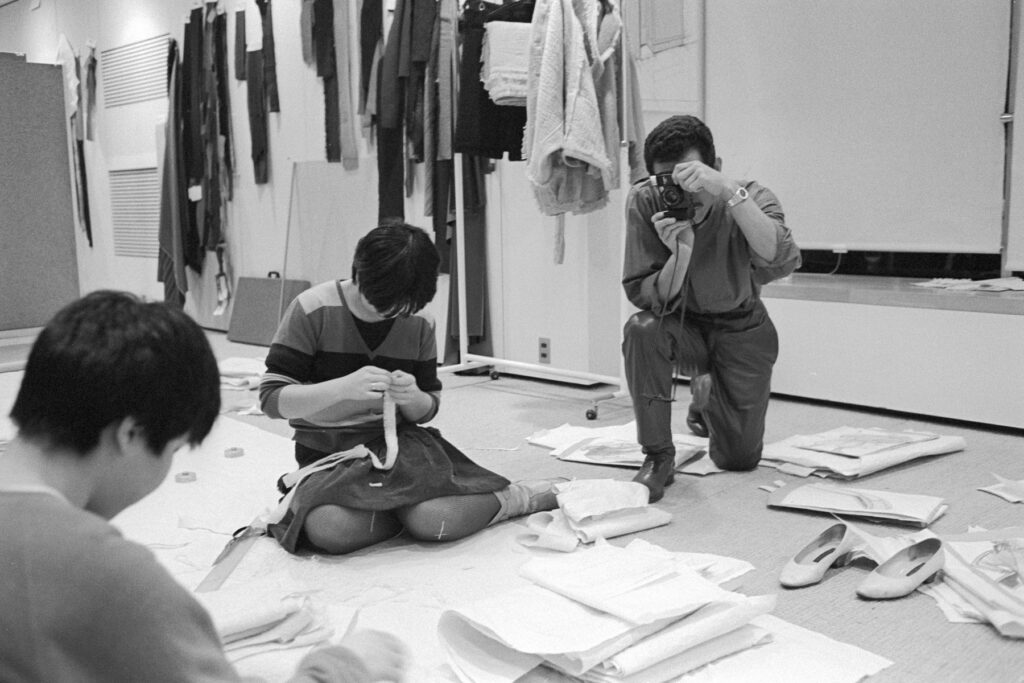

Issey Miyake’s Studio in the late 1980s–90s

From 1971, he unveiled in New York a first ready-to-wear collection. This baptism by international fire took place under the benevolent eye of Diana Vreeland, Vogue’s famous editor, who recognized in him a visionary. Then in 1973, Issey Miyake was invited to present his work in Paris. It was the first time a Japanese designer made such an impact in France since Kenzo. The following year, he even became the first foreigner officially integrated into the Paris show calendar. Paris, which had once rebuffed Yamamoto before adoring him, greeted Miyake with curiosity then fervor. His innovative style, inspired as much by hippie freedom as by Japanese tradition, intrigued: he offered light, modular clothes, ennobled by unprecedented materials and a sense of comfort never seen in haute couture.

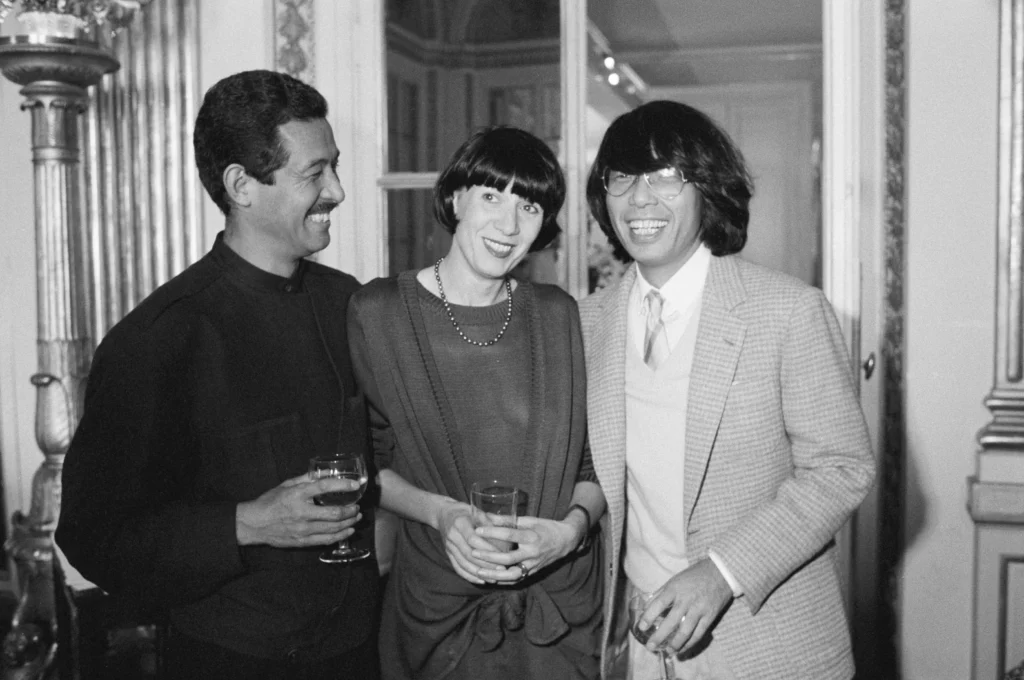

Issey Miyake, Chantal Tomass et Kenzo, à Paris, en 1984 photographed by Micheline Pelletier

Issey Miyake had a very clear philosophy of clothing: for him, a garment should be a natural extension of the body, to facilitate movement and life. “All my research has always been centered on movement and the freedom allowed by the garment. The person who wears it gives it its final dimension,” he affirmed, stressing that design is only complete through interaction with its wearer.

This view perhaps sprang from his survivor’s experience: having known enforced stillness through illness, he felt a deep desire to free motion. In his studio, he worked like an alchemist of materials. He ceaselessly experimented with new fabrics, drawing on both traditional Japanese techniques and cutting-edge technology. His ambition was to reconcile tradition and future, body and garment, art and daily life.

Irving Penn’s “Woman in a Miyake Raincoat” – 1998

One of the great revolutions he brought was the art of modern pleating. From 1988, Miyake developed a novel heat pleating technique that would give birth to his legendary Pleats Please line in 1993. Miyake’s pleats are far more than aesthetic adornments: they are living structures that accompany body movement and capture light vibrantly.

Colorful Pleats Please Collection

“My work is about the construction of the space between the garment and the body,” he explained, to convey his architectural approach to textiles. Freeing that space meant allowing the body to breathe, to move, to fully exist without constraint, and light to flow around the being as in an open temple. With his wrinkle-proof pleats, his innovative weaves and generous cuts, Miyake truly transfigured the perception of the body in fashion. Where once clothing corseted and molded by force, he made room for emptiness and flexibility, so each individual could inhabit the garment as they pleased.

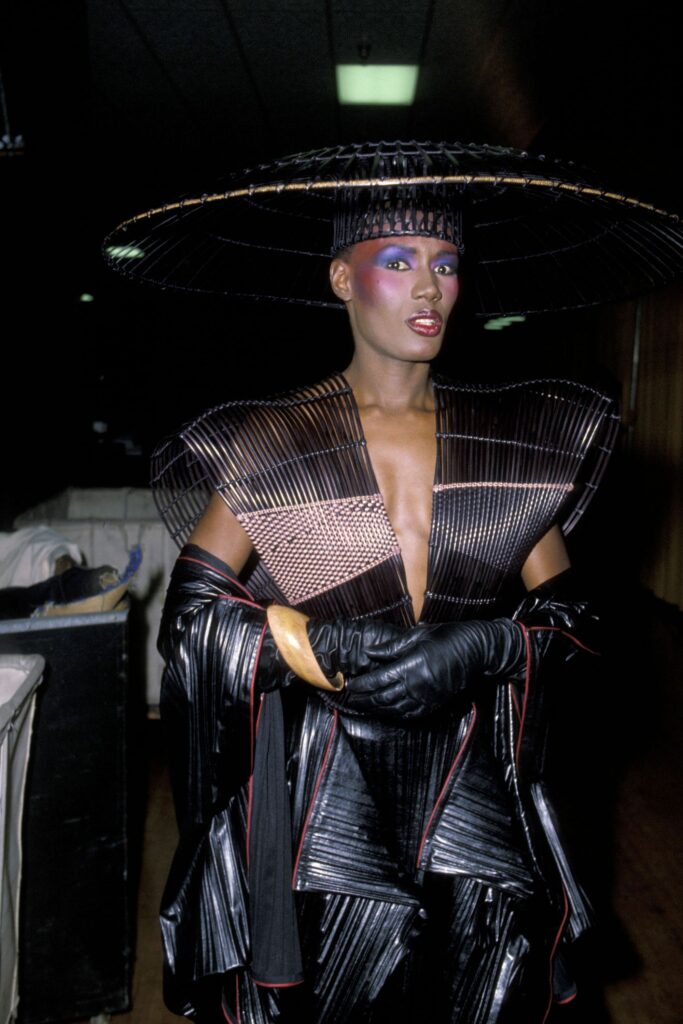

Grace Jones’s 1983 Grammys Issey Miyake Ensemble

Throughout his career, Issey Miyake enjoyed great triumphs. In 1999, after building a creative empire, he presented his last collection as head of his house, before passing the torch to his disciples and dedicating himself to new projects. He launched his iconic perfume L’Eau d’Issey, the olfactory embodiment of his quest for purity, just before retiring from the main stage. In 2005, he received the Praemium Imperiale, considered the art world’s Nobel in Japan, the ultimate recognition of his cultural contribution. He also established a design foundation to transmit his knowledge and continue innovating beyond runways. His creations were celebrated in museums worldwide, from New York’s Metropolitan Museum to London’s Victoria & Albert Museum.

Issey Miyake – SS99 “Connected” Red Dress (A-POC)

When Issey Miyake passed away in 2022 at age 84, the world emotionally saluted the spiritual legacy of this man who sublimated tragedy into beauty. His fundamental avant-garde principle is doubtless the liberation of the body through joyful innovation. Where other avant-gardists chose provocation or darkness, Miyake chose the path of light and constructive positivity. He transformed how we perceive individuality in fashion: to him, each person carries creativity, and clothing should partner with that personal creativity, not hinder it. Through his modular garments, he infused the idea that attire can evolve with the person, adapt to their movements and moods, far from fixing identity, it reflects its dynamism.

Issey Miyake – AW25

Reflecting on the path of Issey Miyake, one embraces a philosophy of resilience and boundless creativity. His journey teaches that from the greatest pain can spring a fierce will to build beauty and newness. Each pleat in our lives, each scar can become a motif of embellishment, like his pleats that turn constraint into grace. He invites us to seek unprecedented solutions where everything seems destroyed, to unite the wisdom of the past with future techniques to invent our own way. In our daily lives, to draw inspiration from Miyake is to seek comfort without forsaking elegance, to believe in the power of innovation to enhance common well-being. His ultimate lesson is a hymn to life that continues, to the ceaseless movement of being. May each of us open in our heart a workshop of light, to patiently weave the fabric of a better future, that is the most precious homage we can pay to Master Issey, bearer of dawn and peace.

Issey Miyake photographed by Irving Penn in New York -1988