How Japanese Designers Shaped the Future of Avant-Garde Fashion

Japanese designers redefined avant-garde by merging tradition, philosophy, and innovation. From deconstruction to minimalism, their influence reshaped Western fashion and continues to inspire a generation seeking authenticity over perfection.

Through decades of innovative creations and bold designs that have compelled critics and onlookers to reconsider the relationship between fashion, art, and design, Japanese designers have reshaped ideas and cultural boundaries between Eastern and Western notions of clothing.

Japanese influence in Western fashion dates back nearly a century. After World War II, Japan entered a period of rapid modernisation and Westernisation. This prompted Japanese artists and designers to incorporate Western art movements, such as Pop Art and Minimalism, into their own traditions, laying the groundwork for the future of Japanese avant-garde design. By the late twentieth century, names like Rei Kawakubo, Issey Miyake, Kansai Yamamoto, and Yohji Yamamoto had firmly established themselves on the global fashion stage.

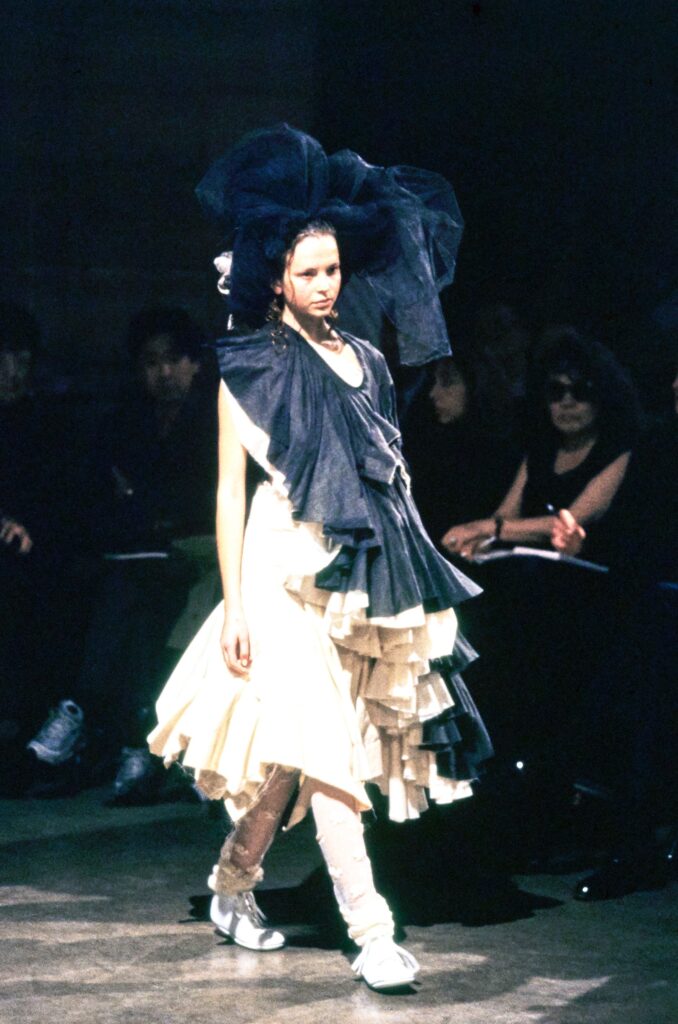

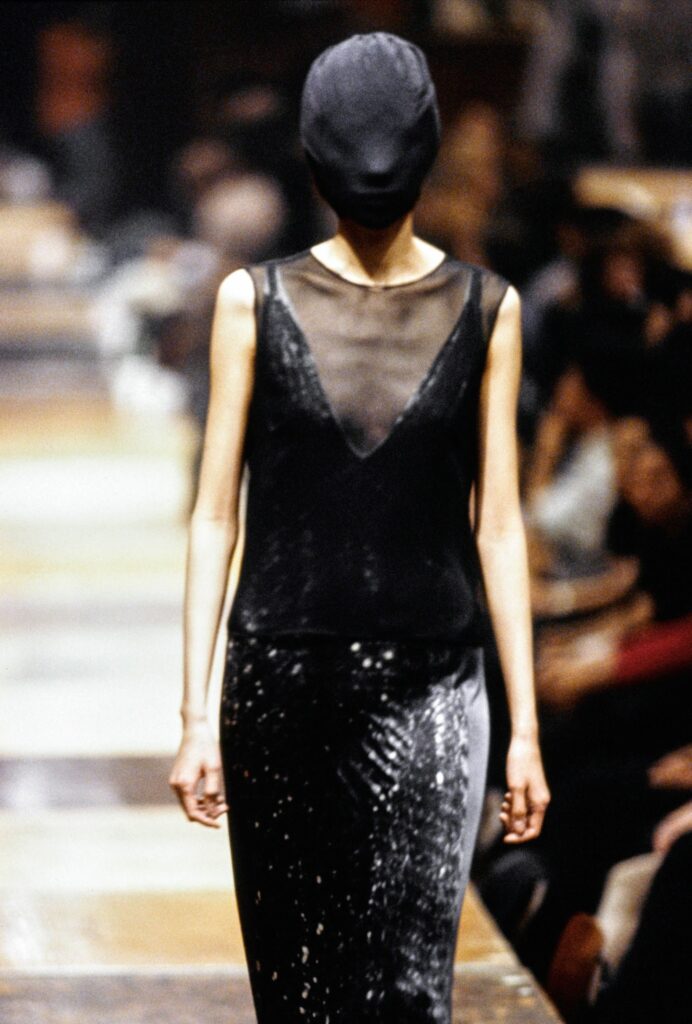

Yohji Yamamoto, FW98

In the 1970s, the second-wave feminist movement brought a shift in dressing, as women moved away from restrictive silhouettes and the fantasy of primness toward looser, more liberated forms. In the 1980s, Kawakubo and Yohji took to Paris after years of showing in Tokyo, presenting designs that were raw, deconstructed, and rendered in muted colour palettes—an antithesis to the decade’s excess.

At first, the reaction was far from favourable. Critics dismissively dubbed the duo’s work “Hiroshima Chic,” comparing the aesthetic to the devastation of Hiroshima. Yet not everyone was hostile. Polly Mellen, then editor of American Vogue, praised the pair’s work as “modern and free,” declaring: “It has given to my eyes something new and has made this first day incredible. Yamamoto and Kawakubo are showing the way to a whole new way of beauty.”

Comme des Garcons, SS98

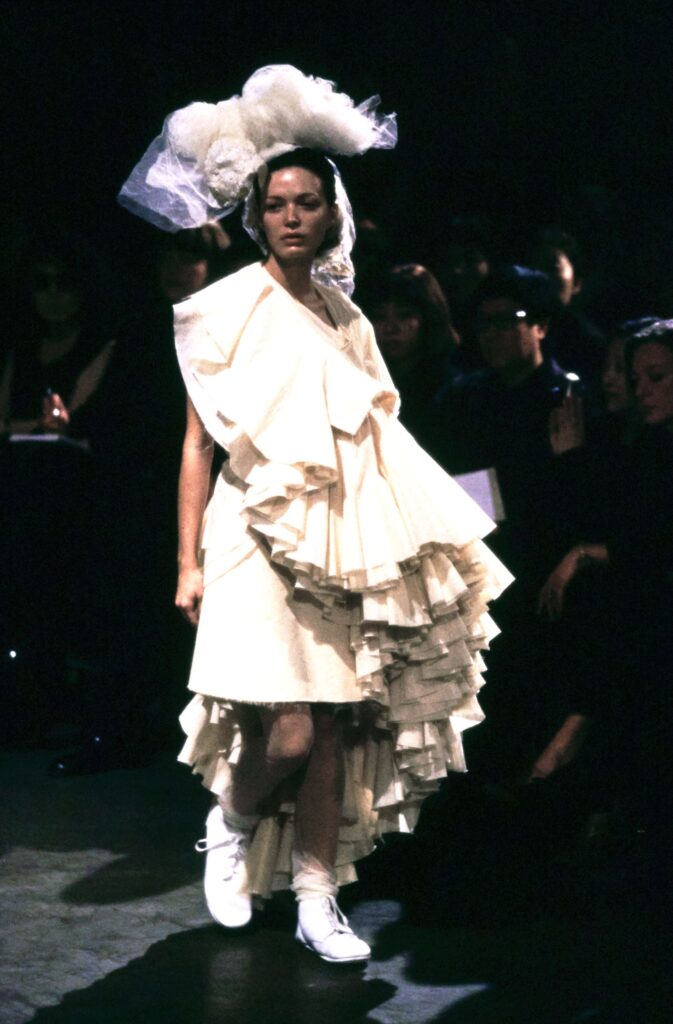

Kawakubo, Yamamoto, and Miyake stood in stark contrast to European contemporaries like Gianni Versace, who championed glamour, sex, and power. Instead, the Japanese designers brought intellectual depth and philosophical nuance. In a 2009 New York Times essay, Miyake admitted that his optimistic approach to fashion stemmed partly from surviving the 1945 Hiroshima bombing: he preferred “to think of things that can be created, not destroyed.” Until his passing in 2022, he rejected labels such as “artist” or “Japanese fashion designer,” even as his pioneering exploration of technology and fabric manipulation left an indelible mark.

One of Miyake’s most famous contributions was Pleats Please, a collection using lightweight polyester pleated after the garment’s construction. The pleats were heat-sealed, ensuring durability, wrinkle resistance, and practicality. These designs remain beloved more than thirty years later, with British Vogue reporting in 2024 that Depop searches for Pleats Please were up 39%. Miyake also helped introduce Japanese techniques such as shibori (tie-dye), sashiko (needlework), and origami into Western fashion. In many ways, what the West recognises as avant-garde often extends directly from Japanese traditions.

Issey Miyake, SS95

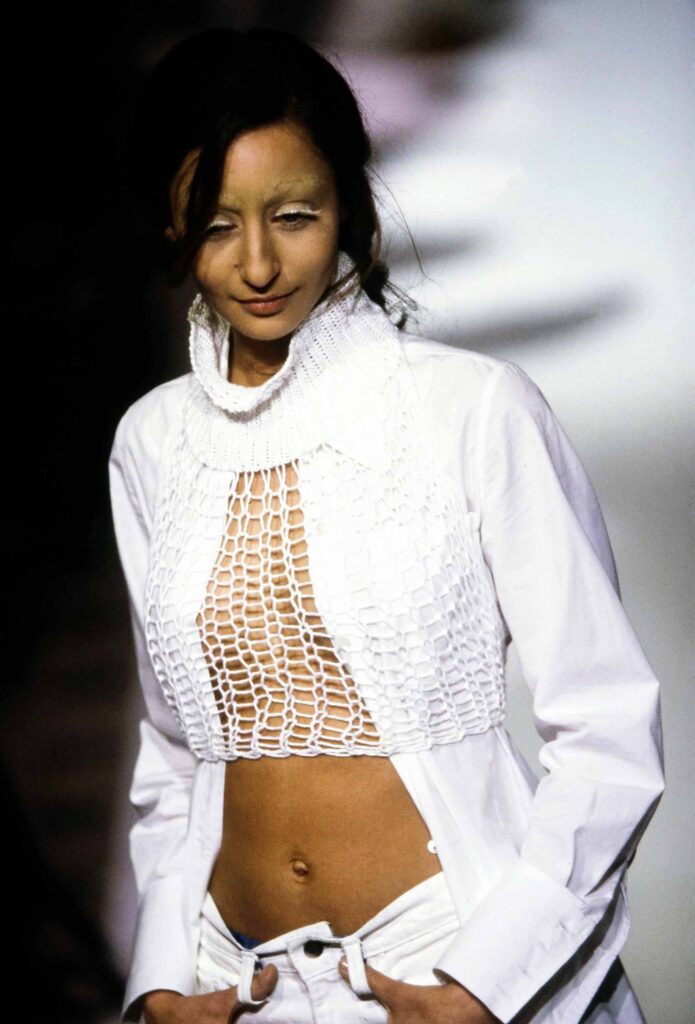

The radical ideas of Japanese designers—deconstruction, oversized proportions, asymmetry, knots and bows as fastenings, unisex garments, voluminous fabrics, and monochrome palettes—inspired a new generation abroad. The “Antwerp Six” (Dries Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester, Walter Van Beirendonck, Dirk Bikkembergs, Dirk Van Saene, and Marina Yee) carried these concepts forward in Belgium.

Ann Demeulemeester, SS97

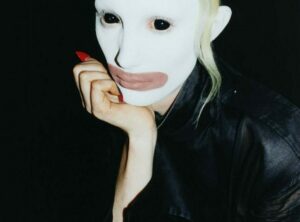

Ann Demeulemeester, in particular, shared Kawakubo’s commitment to monochrome and experimentation with cut, using fashion to question stereotypes of beauty and gender. Martin Margiela, another Royal Academy alumnus, drew directly on the spirit of deconstruction, leaving chalk marks and basting stitches visible. His now-iconic Tabi shoe, inspired by Japanese split-toe socks traditionally worn with sandals, stands as one of the clearest symbols of cultural crossover.

Maison Margiela, SS96

Japanese designers have endured not only because of their originality, but because of their adaptability—whether through technological innovation, collaborations, or championing new talent. Kawakubo expanded Comme des Garçons into more than a dozen diffusion lines, from Homme Plus to Play to Parfums. In 2017, The Met’s Costume Institute dedicated its annual exhibition to her, Rei Kawakubo / Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between, the first to honour a living designer since Yves Saint Laurent in 1983.

Yohji Yamamoto, meanwhile, broke into the mainstream in the early 2000s by partnering with Adidas to create Y-3, a line of avant-garde sportswear that combined minimalist design with bold silhouettes and innovative materials. This move helped bridge the gap between East and West by offering garments that were both commercially viable and aspirational.

Adidas x Y-3, 2020

Through the global success of Miyake, Kawakubo, and Yamamoto, Japan has become a leader in fashion and has paved the way for designers such as Junya Watanabe, Junko Koshino, and Kei Ninomiya. Each continues to weave traditional Japanese sensibilities into expressive avant-garde work, carrying forward the legacy of their predecessors.

While Western houses often chase trends, Japanese avant-garde design has always looked inward, rooted in authenticity and fundamental truths about creativity and human emotion. This is why Japanese designers have not only shaped the future of avant-garde fashion, but will continue to define it for years to come.

Credit

Written by Phoebe Cotterell @_phoebe_alice