Heavenly Bodies Revisited: Fellini’s Vatican Runway, Modern Fashion, and Our Obsession with Religious Spectacle

While the recent media frenzy around the Vatican might have cooled off, fashion keeps returning to Catholic imagery, and perhaps that is no coincidence.

We live in a time of spiritual ambiguity and aesthetic maximalism. In the wake of pandemic-era isolation, political turmoil, and institutional distrust, we seem to be craving transcendence, but not necessarily through faith. Instead, we look for meaning in images, symbolism, and spectacle. Fashion, with its rituals, hierarchies, and visual drama, becomes a kind of secular liturgy. And no religion has offered richer iconography than Catholicism.

This cultural moment might explain why Federico Fellini’s semi-autobiographical 1972 film Roma (not to be confused with Alfonso Cuarón’s film of the same name), particularly its now-iconic clerical fashion show, feels more relevant than ever.

It is perhaps one of his hardest works to describe, composed of loosely connected vignettes set in the Italian capital, without a clear plot or a recognizable protagonist other than the city itself. Yet precisely because of this, it feels enigmatic and fascinating. Roger Ebert gave it four stars out of four and ranked it ninth on his list of the ten best films of 1972. To this day, Roma is remembered not only for its unusual narrative but also for its wicked sense of humor and powerful imagery, brought to life in collaboration with cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno.

The most memorable segment is without a doubt the film’s climax: a scathing and hilarious clerical fashion show that echoes an earlier scene featuring prostitutes parading before eager clients. In it, dozens of clergy and nobles look on as nuns, priests, sacristans, and cardinals strut around a dimly lit hall in increasingly outlandish ensembles while ominous organ music plays. Bird-shaped cornettes, sports tunics, light-up chasubles, and mirrored mitres are just some of the extravagant garments on display.

Federico Fellini’s Clerical fashion show in Roma, 1972

Though exaggerated, the scene resonates with modern-day Catholic spectacle. The recent conclave this past May, the most “stanned” and memed to date, sparked a media frenzy few anticipated. Admittedly, the timing was perfect: the film Conclave had come out a few months prior and became a serious Oscar contender. But this time, not even the traditionally secretive process of electing a new Pope could escape the internet’s grip. Both Catholics and non-Catholics were glued to their screens for two days, or over two weeks if counting Pope Francis’ passing. Streaming services scrambled to add titles like The Young Pope to their catalogues. Harry Styles was allegedly spotted among the crowds in Vatican City. Meme account Pope Crave (yes, that exists) became the go-to source for conclave updates. For the first time, the papal election felt less like a secret ritual and more like an exclusive fashion show: its date, time, and place widely publicized, yet accessible to only a chosen few.

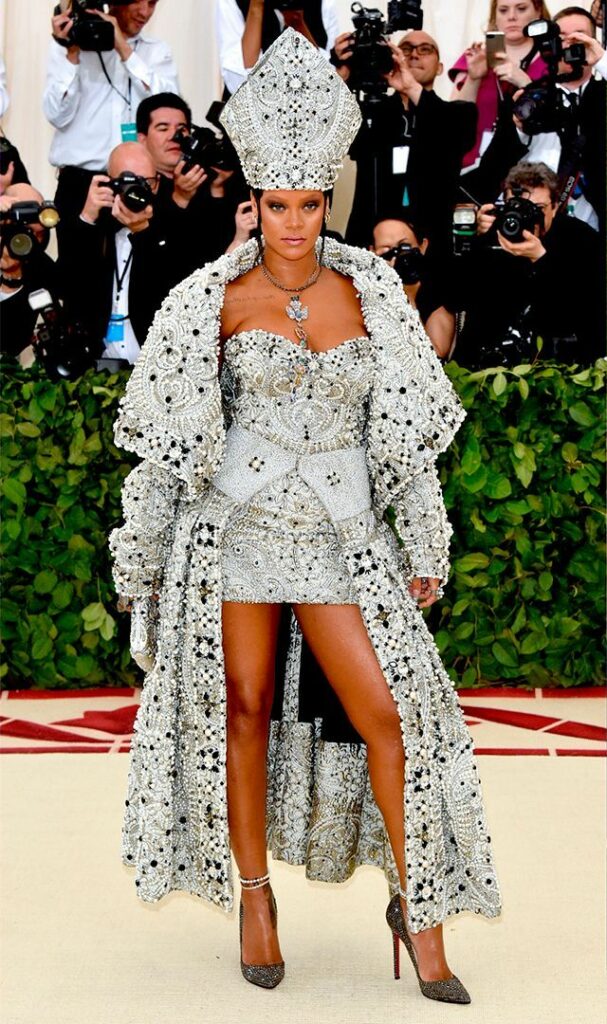

Shortly before the conclave, another high-profile event took place: the Met Gala. This year’s theme, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, was timely and compelling, but one wonders whether resurrecting the 2018 Heavenly Bodies theme might have ridden the wave of Vatican mania even more effectively. Of course, fashion has often drawn on Catholic imagery. John Galliano’s Dior Fall 2000 Couture show famously featured an angry-looking pope flinging incense on the runway, a motif he revisited for Margiela at the Heavenly Bodies gala, worn memorably by Rihanna. A cornette-wearing model dressed in green recalled Fellini’s nuns. All this unfolded to soundtracks from Eyes Wide Shut and A Clockwork Orange.

Rihanna at the “Heavenly Bodies” MET Gala, wearing John Galliano for Margiela inspired by papal attire, 2018

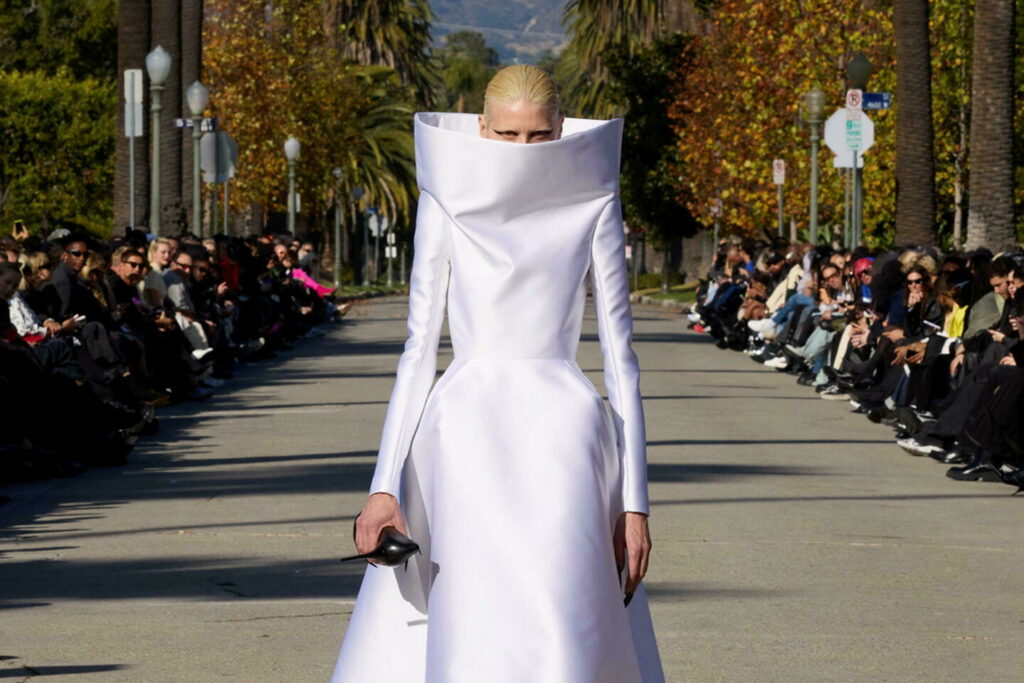

Dolce & Gabbana, meanwhile, have woven Sacred Heart motifs throughout their Alta Moda collections since 2012. And Demna’s Balenciaga, which recently saw the creative director’s departure, has brought monkish hoods and ecclesiastical silhouettes to the catwalk. Even Cristóbal Balenciaga himself, a devout Catholic, often drew on ecclesiastical aesthetics for his designs, some of which appeared in the Heavenly Bodies exhibit. Other designers showcased there included Rick Owens, Valentino, Jean Paul Gaultier, Gareth Pugh, Alexander McQueen, Philip Treacy, Versace, Christian Lacroix, Yves Saint Laurent, Rosella Jardini for Moschino, and Thierry Mugler.

The Sacred Heart was one of the Dolce & Gabbana SS15 collection’s motifs.

Liturgical design by Demna for Balenciaga, FW2024

As expected, the 2018 exhibit faced backlash from nearly 600 protesters across multiple religious groups, who deemed it blasphemous. Sacred-themed fashion often provokes controversy, so no surprise there. Protesters took particular issue with sacred vestments loaned from the Vatican being displayed alongside what they described as “indecent fashions of ‘Catholic’ imagination.” While some individual Met Gala looks may have appeared irreverent, the exhibit itself was meticulously curated. Contemporary fashion pieces were juxtaposed with medieval and Byzantine religious iconography, striving for both historical and conceptual accuracy. Sometimes it was genuinely hard to distinguish sacred from profane. Even Cardinal Dolan, Archbishop of New York, offered his blessing to the exhibition, summarizing Catholic imagination in three words: truth, goodness, and beauty. “That’s why we’re into things such as art, poetry, music, liturgy, and yes, even fashion,” he said at the press preview, “to thank God for the gift of beauty.”

“Heavenly Bodies Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” expo at the MET, 2018

We should distinguish art with a deliberately blasphemous intention, such as a Marilyn Manson album cover, from works that challenge beliefs or provoke discussion. Think of works of fiction like The Last Temptation of Christ, The Young Pope, or Conclave, which explore provocative scenarios without necessarily intending to mock faith outright.

The Young Pope, 2016

Even that distinction is open to debate. Many religious artworks once considered scandalous now sit comfortably in museums. Kramskoi’s Christ in the Desert was criticized for depicting Jesus as merely human, while Dalí’s surreal Madonna of Port Lligat, modeled on his wife Gala, received Pope Pius XII’s blessing in 1949.

Nor should we underestimate the Church’s own cultural openness. In 1995, the Vatican compiled Some Important Films, a list of 45 movies divided into three categories: religion, values, and art. Among them were Nosferatu, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Fellini’s La Strada and 8½, several works by Tarkovsky and Bergman, and notably Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew. Yes, the same Pasolini who directed Salò, one of cinema’s most notorious and obscene films, was a devout Catholic who created one of the most respected biblical adaptations, earning praise from the Church. Likewise, French designer Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, known for dressing Madonna, designed the rainbow vestments worn by Pope John Paul II and 5,500 clergy at World Youth Day 1997. Ironically, this was the same Pope who had previously condemned Madonna’s Blond Ambition Tour.

Castelbajac’s Rainbow Vestments for the Archbishops’ mass (5,500 clergy) at the Longchamp racetrack, 2007

The idea that fashion’s use of religious imagery amounts to cultural appropriation feels misguided. Western societies, especially Southern Europe, are steeped in Catholic iconography; it is part of the cultural bedrock, regardless of personal belief. Restricting its artistic use would be like forbidding references to Greek mythology or proverbs.

Ultimately, our current fascination with religious aesthetics may reflect a deeper cultural longing. The Catholic Church, followed by 1.4 billion people, has always navigated a tension between spiritual austerity and visual grandeur. But some of its symbolic language has been lost in the wake of the Vatican II reforms, which ushered in a more stripped down, minimalist form of worship. If anything, Pope Francis’ papacy made very clear that fashion choices can carry political weight. Fellini, raised Catholic and identifying as such throughout his life, understood this paradox. His clerical runway, like so much avant-garde fashion, satirizes but also celebrates both devotion and decadence.

And if fashion moves cyclically between excess and restraint, it seems we have entered a maximalist moment, one that seeks transcendence in the mystical, the theatrical, and the divine. Religious aesthetics offer not only visual drama but emotional clarity: symbolism that gives shape to our inner turmoil. Maybe that is why people now take to the streets and social media not just to protest, but to perform collective yearning or to “manifest.” A kind of secular prayer.

I wonder what the Pope thinks of Pope Crave.

Alta Sartoria by Dolce Gabbana, 2025

Credit

Written by Nacho Pajin @nachopajin